Resource Library

INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT: Cautious Radicals: Public Opinion and Hong Kong’s Democracy Protests

By Craig Charney | Insights | Series II | No. 7 | November 2014

Since pro-democracy protests began in Hong Kong in late September, the ghosts of Tiananmen Square have hovered over Civic Square and the other protest encampments. Thus, despite their clash over the territory’s political future, the students and activists opposed to Beijing’s policies and their foes in the administration, business, and elsewhere have been careful to avoid violent face-offs that could lead to a repeat of the catastrophic conflict of 1989.

Both sides in Hong Kong are constrained by the power of public opinion there. In that divided society, the pro- and anti-government factions are struggling to win over an ambivalent middle. Moreover, beyond their political divisions, residents broadly share a desire to preserve Hong Kong’s unique rule of law and privileged status within China.

Anger at Beijing’s proposed electoral reform, considered insufficient, along with discontent at the city’s unpopular leader, triggered the protests. But this has been offset by protest fatigue and political disillusionment. Given this situation, and Hong Kong’s distinctive civic culture, there is a possibility for compromise. But the situation is volatile, and a misstep – particularly the large-scale use of force against protesters – could produce a major confrontation.

Hong Kong’s crisis illuminates the political challenges – and stakes – facing the city-state and China as a whole. The situation in the special region shows the steadily growing tensions that develop as the products of modernization – a lively civil society, a free press, and an educated citizenry – chafe under one-party rule. This problem will only deepen in years ahead as a dissenting younger generation comes of age. It tests whether China will accept the consequences of its commitment to “one country, two systems” — or crush Hong Kongers’ democratic aspirations at great cost to the city and the country.

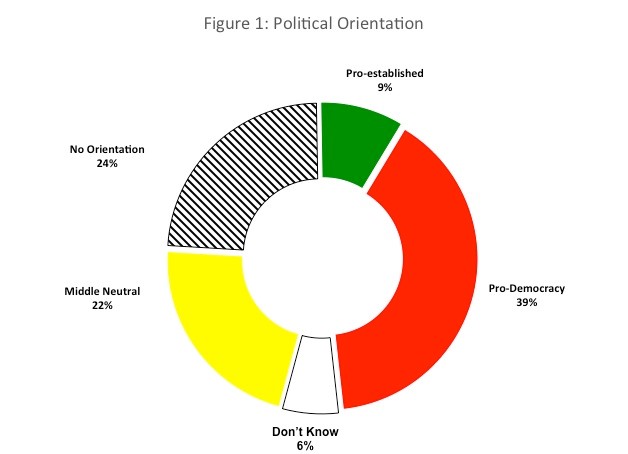

The public in Hong Kong is split, and the result is ambivalence on the key issues facing the territory.

Source: Chinese University of HK Poll, 9/10-17, 2014

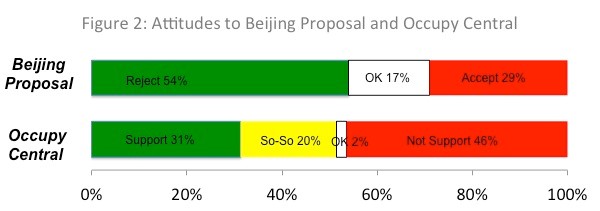

Source: Chinese University of HK Poll, 9/10-17, 2014

A September poll by the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CHUHK) found that the majority of residents (54%) are not in favor of central government’s proposal for the election of Hong Kong’s next Chief Executive in 2017. This plan would make the 1,200-member pro-Beijing committee which chose the Chief Executive until now the sole body for nominations, which opponents say would make sham out of a subsequent popular vote for the post. Only three in ten support it.

Yet the majority also is not in favor of the Occupy Central movement, which has staged ongoing mass protests at several locations. Only three in ten said they backed the protests in the same poll.

So Hong Kongers divide three ways: roughly one-third against the plan and favoring protests, around one third accepting the plan and opposed to the protests, and one third hostile to or unsure about the plan AND the protests. To prevail, both sides know they must win over, or at least not alienate, the middle ground.

But Hong Kong residents also share common ground. They are proud of the freedom and rule of law they enjoy under the Basic Law agreed before Britain’s return of the territory to China in 1997. In a 2012 Gallup global poll, the territory had the sixth-highest rating for safety worldwide and the fewest complaints of corruption among comparable countries. Hong Kongers appreciated this, too: only 4% were considering emigration, one of the lowest figures on Earth. They knew they had something to lose.

Moreover, while most oppose the proposed electoral change, the public is also sick of the protests. A poll by Hong Kong University’s Public Opinion Program (POP) in early November found 70% of Hong Kongers said Occupy Central should stop its occupations.

And the prolonged impasse has also left them feeling cynical about politics more generally. In late October, with protesters still in the streets, POP reported that all major political groups –pro- and anti-Beijing – had all dropped to their lowest recorded popularity scores. (The only exception was the student group leading the protests.)

Disaffection has spread to the regional government, whose rating in the POP survey was the worst since the 1997 handover. The same poll found C.Y. Leung, the current Chief Executive, was at the nadir of his four years in office, with just 23% support.

Hong Kong has faced similar conflicts before, thanks to its lively civic life, with political, trade union, youth, and other organized groups as well as a large degree of press freedom, all unknown elsewhere in China. This has forced the authorities to tread carefully in the face of public opinion. Earlier mass protests – in 2003 and again in 2012 – forced them to back down on unpopular proposals.

In these circumstances, there may be room for compromise. Hong Kongers do not demand instant democratization: POP polls all year long have found consistent support for a “three-track” system, allowing nominations by the committee, political parties, or citizens. If this is too hard for the authorities to swallow, another possible compromise that has been suggested involves expanding or democratizing the selection committee, so it is no longer just an echo chamber for central government. Leung has hinted at this in public statements.

But the situation is delicate, and a misstep by the authorities could result in the conflagration both sides dread. A police assault against protesters back in September brought hundreds of thousands into the streets to protest the breach of civic order. Large-scale violence to remove the protests, even under color of injunctions brought by the courts, may have a similar effect, leading to a brutal crackdown that could damage Hong Kong’s special status.

As a result, Hong Kongers are worried. In September, POP reported that a majority (56%) had lost confidence in the city’s “one country, two systems” arrangement for the first time since its return to China. CHUHK reported the same month that 21% were considering emigration – a huge jump from the 4% Gallup had found two years ago.

Yet postponing change will only increase the pressure for it. The surveys confirm what can be seen in the streets: the generation gap in Hong Kong is a chasm. Unlike their elders, under-30s reject the official electoral proposal and support the Occupy movement and its continuation in massive proportions. The same is true for those with secondary or tertiary education. As they grow in numbers and influence, the pressure on China’s ruling Communist party in Hong Kong will rise as well.

Hong Kong has become a test case for whether China can accommodate the political and social forces unleashed by its breakneck development. If it can find a modus vivendi with the turbulent territory, its chances of peaceful change will increase markedly. If not, the failure of “one country, two systems” there will cast the shadow of Tiananmen once more over Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Chinese mainland itself.

Craig Charney is president of Charney Research and research director of China Beige Book, a quarterly economic survey of the People’s Republic of China.

Other articles you may like:

Inside China’s Black Box of Statistics

How a Beige Book Could Shed Light on China’s Shadow Economy

China’s New Open Door: The E-Commerce Boom